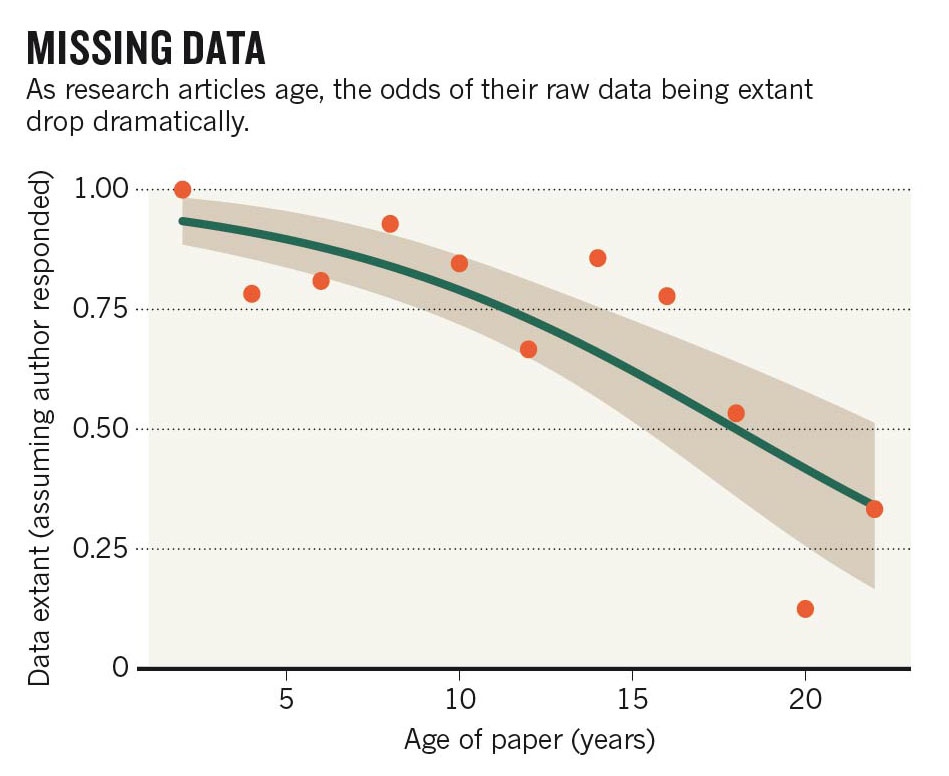

The journal Current Biology published a paper yesterday that proves what may be obvious to many of us: we’re really bad at keeping track of old data. Not only is it difficult to maintain data, particularly digital data, for many years but researchers are not trained in how to preserve our information. The result is a decay of data availability over time.

This decay not only hurts us, the original data producers, by limiting opportunities for our own data but it also hurts others in our field. The Nature commentary on the original article provides a great example of why this is, citing an ecologist who works with a plant studied 40 years ago by another scientist. Because the older data are now lost, the first ecologist cannot make any useful conclusions about the plant over the long term.

In the Nature commentary example, the original scientist is now dead but his data are still valuable, meaning that data are often assets to be cared for long after we are alive and need them. To address this, one scientist has suggested we develop scientific wills, of sorts, to identify datasets of value in the long term and who will care for them. No matter what, we need to start thinking about our data in the long term.

I’m not saying that every scientist needs to be an expert in digital preservation, but it does help to know the basics of keeping up with your data. Still, the best way to preserve data in the long term is by giving it to a preservation expert (aka. a data repository) to manage. This way, you don’t have to learn the ins and outs of preservation and you don’t have to worry about keeping track of the data yourself. It’s just what every scientist wants: a hands-off system that keeps track of your data while costing little to no money.

Data repositories come in two major flavors: disciplinary repositories run by an outside group and your local institutional repository run by your library. Either way, it’s their whole job to make sure that whatever is in their repository is available many years from now. I suggest starting with your local repository when looking for a home for your data, but be aware that many of these repositories were built for open access articles and cannot handle large datasets. In that case, consider one of the follow repositories:

- DataONE (environmental science)

- Dryad (biology/general)

- figshare (general)

- GenBank (gene sequences)

- github (code)

- Harvard Dataverse (science)

- ICPSR (social science)

These repositories make data openly available because many journals and fields are coming to expect data publication alongside article publication. Still, it’s possible to upload your data and embargo it for a short period of time, allowing you to keep working with the data but not worry about preserving it. The repository figshare even has a new private repository feature, which I think is pretty cool: it keeps your data private (and privately shareable) for any amount of time but lets you easily switch a dataset to public when you need to.

This list represents my repository highlights but there are obviously many more available, especially in biology. Ask around to find out if there is one your peers prefer, which will make your data more likely to be found and cited.

Finally, I will add that we will be seeing much more about data repositories going forward. Between journal and funder requirements to publish data and the recent White House OSTP memo pushing for even more data sharing, data repositories and data publications are only going to grow from here. If it means that we stop hemorrhaging data over time, I think that’s a very good thing.

Pingback: New Federal Grants Guidance and How It Effects Data » Data Ab Initio